Wikipedia Founder Warns AI Threatens Facts

The man who built the internet’s library is now ringing the fire alarm. Jimmy Wales, the co-founder of Wikipedia, has a stark warning for the digital age he helped create. The threat isn’t state-sponsored trolls or lone-wolf vandals anymore. It’s the very technology Silicon Valley has anointed as its savior: artificial intelligence.

And his concern is simple. What happens when a machine can write a million convincing lies in the time it takes a human to verify one truth?

For two decades, Wikipedia has stood as a monument, however flawed, to a certain kind of digital optimism. A sprawling, volunteer-edited encyclopedia built on a foundation of citations and a relentless, often nerdy, commitment to the facts. But that human-scale model, Wales fears, is about to be swamped by a tidal wave of machine-generated content that is plausible, persuasive, and, all too often, profoundly wrong.

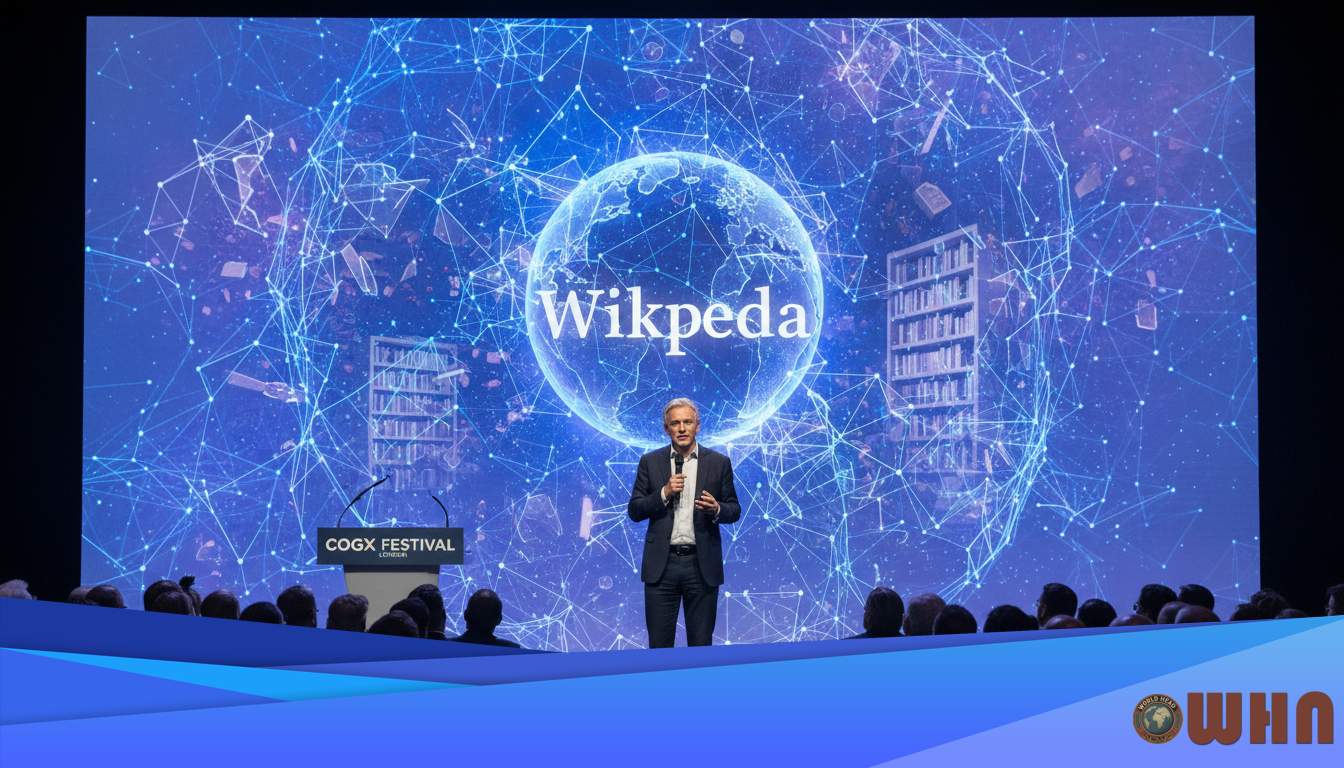

Speaking at the CogX festival in London, Wales didn’t mince words. He described the current state of Large Language Models, or LLMs, as “horrifying.” The issue isn’t just that they make mistakes. It’s that they “hallucinate” with an air of absolute authority, a phenomenon that strikes at the very heart of the encyclopedic project. Wikipedia’s core principle is verifiability. An LLM’s core function, by contrast, is probabilistic text generation. One is a library; the other is a sophisticated mimic.

“We’re going to have to get very, very serious about this,” Wales stated, emphasizing the difficulty of distinguishing machine-made falsehoods from human-curated knowledge.

This isn’t a theoretical debate for a university seminar. It’s a live fire exercise happening on the world’s largest information platforms. Look at Google. The company’s recent rollout of AI Overviews in its search results produced a string of embarrassing, and potentially dangerous, errors. The AI confidently advised users to put non-toxic glue on pizza to keep the cheese from sliding off, a recommendation it sourced from a joke comment on Reddit. It suggested eating at least one small rock per day, citing a satirical article from The Onion.

These aren’t just funny gaffes. They are symptoms of the disease Wales is diagnosing. An AI, tasked with summarizing the internet, cannot yet reliably distinguish between a peer-reviewed scientific paper, a government database, and a decade-old joke. And when that faulty summary is presented with the authority of a Google search result, the potential for harm is massive.

The Battle for Wikipedia’s Soul

The threat to Wikipedia is particularly acute. The platform’s strength—its openness to editing by anyone—is also its greatest vulnerability. A small army of dedicated volunteer editors currently fights a constant battle against vandalism and disinformation. They are, in effect, the human immune system of the project.

But AI changes the scale of the attack. Imagine a botnet capable of generating thousands of subtly incorrect but well-written articles on obscure historical figures or complex scientific topics. Each article could be complete with fake, but plausible-looking, citations. The human editors, already stretched thin, could be completely overwhelmed. The very signal of trust Wikipedia has built over 23 years could be eroded from within.

Wales is clear that AI has its uses. He sees potential for AI tools to help human editors, for instance, by identifying contradictions between two articles or flagging text that lacks a citation. It could be a powerful assistant. But the danger, he insists, is when the AI moves from assistant to author. A machine, in his view, shouldn’t be writing encyclopedia entries because it doesn’t “understand” truth; it only understands patterns in data.

This is where the business editor’s lens becomes critical. What we’re witnessing isn’t just a philosophical debate about the nature of truth. It’s a high-stakes business struggle over who controls the flow of information, and how it’s monetized.

A Different Kind of Network

Wales isn’t just complaining from the sidelines. He’s putting his money where his mouth is with a project called WT.Social. It is, perhaps, one of the most anti-Silicon Valley social networks imaginable. Launched as an alternative to the algorithm-driven ecosystems of Facebook and X, WT.Social is funded by user donations, not advertising. There is no “engagement” algorithm force-feeding you content designed to provoke a reaction.

The timeline is chronological. Content is organized into user-moderated “subwikis.” It’s slow, deliberate, and entirely focused on human curation. It’s a business model built on trust, not on clicks. Its user base is a fraction of the size of Meta’s or TikTok’s. It’s a tough sell in a world addicted to the dopamine hit of the infinite scroll.

But the existence of WT.Social, and its sister project WikiTribune, serves as a clear statement of intent. Wales believes a different model is possible. One where the incentives are aligned with providing quality information, not with harvesting user data for advertisers. He argues that the ad-based revenue model is the original sin of the modern internet, creating a system where “crazy, hateful, conspiratorial nonsense” often gets more distribution because it generates more clicks.

The business challenge is whooping. WT.Social has to convince users to pay for something they are used to getting for free. It has to compete with tech giants that have billions to spend on research, development, and marketing. It is, by any measure, a long shot.

The Trust Deficit

Yet the timing of Wales’s crusade couldn’t be better. Public trust in both traditional media and social media platforms has slumped to historic lows, polls from organizations like the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism show. People are increasingly aware that the information they consume is being shaped by opaque algorithms designed to serve corporate interests, not their own.

The AI revolution, for all its promise, risks pouring gasoline on this fire. If users can’t trust their search engine to tell them not to eat rocks, how can they trust it with medical advice, financial information, or political facts? The cost of getting this wrong for a company like Google or Microsoft is not just reputational. It’s existential.

Advertisers, the lifeblood of these tech giants, are notoriously risk-averse. They do not want their brands appearing next to AI-generated nonsense that advises people to drink bleach. A sustained loss of user trust would inevitably lead to a loss of advertiser confidence. And that, in turn, hits the bottom line. It’s a direct threat to the multi-billion dollar digital advertising market.

So what’s the path forward? The pressure is mounting on AI developers like OpenAI, Google, and Anthropic to build more effective guardrails. To find ways to ground their models in factual data and to be more transparent about when and how they make mistakes. Regulators in the European Union and, to a lesser extent, the United States are beginning to ask tough questions about accountability for AI-generated content.

The fight, it seems, will be waged on two fronts. One is technological—a race to make AI more reliable and less prone to hallucination. The other is structural—a battle of business models. Can a user-funded, human-curated model like the one Wales champions find a sustainable niche in a market dominated by ad-driven, algorithm-powered giants? The answer to that question may well determine what the internet looks like in the next decade.

For now, the man who gave the world its go-to source for facts is positioning himself as the chief skeptic of its future. The irony is sharp. And for a digital world already drowning in disinformation, Jimmy Wales’s warning is one we ignore at our peril. He remains focused on the core mission that started it all, telling audiences that the goal is to create a space where thoughtful conversation, backed by facts, can actually happen.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute financial, legal, or professional advice. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any other agency, organization, employer, or company.